Dr. Muzzamal Hussain

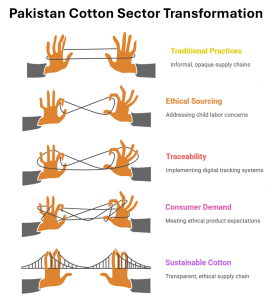

Pakistan’s cotton sector, which drives about 60% of the nation’s exports and sustains over 10 million livelihoods, is navigating intense global pressure for ethical and transparent sourcing. As the world’s fifth-largest cotton producer, it confronts persistent challenges like child and forced labor. The ILO-UNICEF 2024 Global Estimates report nearly 138 million children in child labour worldwide, with around 61% in agriculture, while the U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) 2024 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) list specifically flags cotton from Pakistan for both child labor and forced labor.

Local and Global Perspectives on Child Labor

However, local perspectives in Pakistan often paint a nuanced picture of child labor in cotton farming, differing from global narratives. Farmers, authorities, and community leaders frequently view children’s involvement as a family tradition rather than exploitation. In rural areas, where poverty, large family sizes, and limited access to education prevail, children assist parents on family farms during seasonal harvests, learning essential skills and contributing to household survival. Reports from organizations like the National Rural Support Programme (NRSP) and ILO emphasize cultural acceptance, where child work is seen as non-hazardous family help, not formal labor, especially in Punjab and Sindh. Authorities, including Punjab’s Labour Department, argue that while hazardous forms are addressed, seasonal family involvement stems from economic necessities and migration, not systemic abuse, per baseline studies and policy briefs. International organizations, however, while acknowledging these socio-economic and cultural contexts, stress that much of this family-based work qualifies as child labor if it is hazardous, interferes with education, or exploits children, as per ILO conventions. The USDOL similarly recognizes family dynamics but classifies tasks in Pakistan’s cotton sector as dangerous, advocating for eradication through enforcement and support programs to prevent long-term harm to children’s health and development. As these practices create an atmosphere that make the children an economic asset, which subsequently deprive him from education and in the long run. This viewpoint underscores the need for context-sensitive interventions that support families without stigmatizing cultural practices.

The Role of Traceability in Bridging Perspectives

These contrasting views on child labor highlight the critical role of traceability in bridging local perceptions with global standards, ensuring verifiable evidence of ethical practices from farm to fabric. Traceability is emphasized because it provides transparency into supply chains, helping to identify and mitigate risks like exploitation, while enabling brands to comply with ethical sourcing demands and consumers to make informed choices. This push has intensified due to high-profile scandals, regulatory pressures, and sustainability imperatives, with countries like the EU (through its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive) and the US (via the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act) mandating proof against human rights abuses in imports. Brands such as H&M, Adidas, and those in the Better Cotton Initiative face reputational risks from reports like Transparentem’s 2025 analysis on cotton due diligence, amplifying calls for end-to-end tracking to build trust and premium value.

Rising Consumer Demand and Sustainability Goals

Consumer demand for ethical products has surged, with brands facing reputational risks from scandals involving forced labor. Sustainability goals, like those in the 2025 Sustainable Cotton Challenge, push for transparency amid climate volatility, trade disruptions, and geopolitical tensions affecting supply. Reports from OECD-FAO and World Economic Forum emphasize traceability’s role in building consumer confidence, reducing contamination, and enabling premium pricing for verified sustainable cotton, driving the need for end-to-end visibility.

Digital Innovations in Pakistan’s Cotton Sector

In response, digital innovations are gaining traction in Pakistan as well, though their implementation remains uneven, as detailed in the Sustainable Development Policy Institute’s (SDPI) value chain analyses from 2017 to 2025, which highlights how informal practices dominate small farms and undermine adaptation efforts.

Key Traceability Initiatives

To address these, several key traceability initiatives and tools are being deployed. Initiatives include the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), which focuses on sustainable farming standards and labor rights through community engagement. They not only address social issues but also encompass a broader spectrum: environmental sustainability, quality assurance, fraud prevention, and economic resilience. REEL Cotton by CottonConnect emphasizes a Code of Conduct for sustainable agriculture practices and provides farmer training programme on regenerative farming, environmental impact reduction, and livelihood enhancement. The DOL-funded Global Trace Protocol (GTP) for 2023-2025 pilots cotton supply chains mapping in Pakistan with due diligence frameworks (child and forced labor) and developed an open-source digital traceability tool. WWF’s organic cotton initiatives promote sustainable farming practices, while the ILO’s RISE for Impact Phase II (2024-2026) advances fundamental principles and rights at work through community models and policy advocacy. In addition, several textile industries have started their own programs, such as Artistic Milliners, Interloop, and Masood Textile Mills etc. This new practice by manufacturing industries is gaining more and more attention.

Traceability Mechanisms

Distinct from these initiatives, traceability mechanisms such as bale IDs, QR codes, and blockchain provide technical tracking.

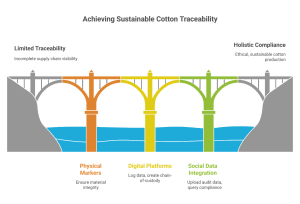

Interlinking Physical, Digital, and Social Traceability:

Physical traceability (e.g., tracers or bale IDs) provides tamper-proof, proof of material origin, acting as the “hardware” foundation. Digital traceability (blockchain, QR codes) overlays this with software layers, recording transactions and data flows immutably. Social traceability integrates labor compliance, verifying conditions like child labor absence or decent work via audits linked to these systems.

The mechanism works through a hybrid model: Physical markers ensure material integrity (e.g., preventing mixing of certified/uncertified cotton). Digital platforms log this data, creating a chain of custody. Social data from audits (e.g., worker interviews) is uploaded, allowing stakeholders to query holistic compliance. For instance, a QR scan on a bale could reveal not just the farm origin (physical/digital) but also audit results on child labor (social).

An example is the Social & Labor Convergence Program (SLCP), which uses a Converged Assessment Framework for standardized social audits in manufacturing facilities. While primarily designed for downstream apparel and footwear supply chains, SLCP could potentially be adapted for upstream segments (farms/gins) by training auditors on agriculture-specific risks, integrating with physical tracers (e.g., linking SLCP scores to bale IDs), and using digital platforms for data sharing. In Pakistan, this could align with ILO’s RISE for Impact Project or GTP Traceability tool, targeting cotton communities in Punjab and Sindh, though SLCP’s current focus is on factories rather than farms. Another example of hybrid system is FibreTrace, which embeds luminescent-based tracers into materials like cotton, r-PET, linen, etc., and then they have a verification system in-place, this can be linked with any digital platform effectively, empowering suppliers such as AGI Denim, Artistic Fabric Mills, Sapphire Textile Mills, Sapphire Fibre, Neela Denim, and Diamond Denim with Good Earth Cotton for real-time verification and authentication of material sources and sustainable cotton bales.

Impacts on the Ground and Way Forward

Despite advancements, ground impacts are mixed.

- Punjab’s 2019-2020 Child Labour Survey shows 13.4% of children aged 5–14 working, with higher rates south punjab. Pakistan has only 636 labor inspectors, far below the 4,259 recommended by the International Labour Organization (ILO), making it hard to enforce fair practices.

- Cellular coverage in Pakistan is very good however, with exceptions of certain remote areas which have limitations of connectivity however there are issues of availability and affordability of smart phones and internet packages as well for low-income formers when it comes to collecting data, Low-cost internet and smartphones should be provided in rural areas.

- Scaling efforts require linking Pakistan Cotton Ginners’ Association (PCGA) systems with tools and providing training to farmers and stakeholders through the ILO and Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), teaching them how to use bale IDs and QR codes.

- Tools like QR codes and blockchain can be expensive for small farmers without support, so the government and international agencies should assist in the transition.

- Mandating traceability through policies, expanding the traceability initiatives, and fostering collaboration could transform the sector.

Why It Matters to Everyone

For farmers, traceability means better pay and respect for their work. For buyers, it ensures ethical cotton. For consumers, it’s about knowing the clothes you wear don’t harm kids or the environment. By blending local traditions with global standards, Pakistan can turn its “white gold” into a leader in sustainable cotton.

Acknowledgement

Mr. Saqib Sohail, Dr. Rubab Batool and Ms. Maira Sheikh Qureshi for help in the review. Ethical sourcing